(Cover art © by Terry Witmer)

Basil Rathbone (1892-1967)Today, August 1, 2010, Turner Classic Movies features the films of Basil Rathbone to start its

Summer under the Stars festival.

In 1975, I worked on the catalogue of the Basil Rathbone Collection for the antiquarian book firm: Gravesend Books. The Proprietress was my wife, Enola Stewart. The catalogue was printed in 500 copies and cast out upon the collector’s waters. The contents virtually sold out in one half hour. Most of the items now reside at Boston University.

It occurred to me that the original Introduction to that long ago catalogue might be of interest. So I have reproduced the text of the original 1975 Introduction (unchanged) into this blog format.

Basil Rathbone: A catalogue of the collection acquired from the estate of Basil and Ouida Rathbone. Including books from their library, personal photograph albums, holograph manuscripts, and letters from celebrities in the performing arts. Also included are scrapbooks, programs, playbills, souvenirs, photographs and ephemera pertaining to their film, stage, television and radio careers. Gravesend Books, 1975. Cover art © by Terry Witmer. IntroductionThe ManBasil Rathbone walked on to a stage in 1912 and played Hortensio in William Shakespeare's

The Taming of the Shrew. In 1967, he walked off a sound stage, having completed the film

Hillbillies in a Haunted House. What happened to the man's life between those two milestones says much about two countries, our times, and the various art forms that his talent encompassed. The course of his life between those events is represented at its various stages by the material listed within this catalogue.

Early research to provide background for this catalogue indicated that printed information on the actor's life was limited to a few sources. Rathbone detailed his own life in an unsatisfactory book and Michael Druxman catalogued the actor's films, and little else, in a book published in 1975 by a house apparently as uninspired by the subject as was the film organization that conceived the actor's last film.

We cannot fault others for not writing the book that Rathbone did not write himself, but I believe that a biography of Rathbone, if an understanding one will ever be written, can only be written by a biographer with solid credentials in the theatre. Until such a book is written, this collection can provide some insight through the study of the source material within it.

Rathbone married a playwright and this is a significant and consistent point in his life. The playwright was a failure in her chosen craft and I suspect Rathbone's own professional life was a failure by his own standards. Throughout this collection is evidence of his discontent. Only in the bright moments and brief successes of

J.B. and

The Heiress do we find a satisfied Rathbone. He succeeded financially, and to many of us, aesthetically, in film. But he was a man of the theatre, disillusioned with film, who would write: "It is the shadow of the substance." He viewed film in that light and appeared unable to take it on its own terms.

He left Hollywood in 1946 and returned to a theatre, which if not unhealthy, was at least poor soil for his own new flowering. He had his moments of new growth, but they were few, and he spent his later years bringing talent and enthusiasm to tired summer audiences who confused Noel Coward for Neil Simon, and to young college students who perhaps carried some light from his

Evening with Basil Rathbone into their later lives.

But Rathbone belonged to the theatre, which by its nature, unlike film, cannot be preserved in its performers but only in its words. Here then he is preserved, within the limits and life span of words and print and fading pictures; of ink on fragile paper and programs and playbills; all of these -- vestiges of a time when young Shakespearean actors were presented to queens.

Pieces of the whole. Fragments of a career. He has crossed his century and the stage work is ended. And if we will have him reside on Baker Street, it will have to be on film. But I feel the loss he may have felt for himself and for all the audiences who never had the privilege of seeing Basil Rathbone on a stage as Sherlock Holmes, or as Judas, or more sadly -- in his and our waning youth -- as Romeo to Katherine Cornell's Juliet.

The WomanOuida Bergere was an established scenarist and a socially prominent member of the film and theatrical community when she met and won the young actor's heart in 1924. Thereafter, as Ouida Rathbone, she was in his shadow but did emerge as a famed party giver, particularly in the Hollywood success period of the late 1930s and early 1940s. She contributed to Basil's career as an advisor and an intermediary. And he adored her.

Throughout the period of their marriage, she wrote a series of unsuccessful, mostly unperformed, plays in a, heavy-handed style that had the essence of being written in magic marker (clutched in) mittens. The plays themselves, with the possible exception of the Liszt piece, lack originality, and are virtually all adapted from other sources, or were the results of inbreeding from her own prior work.

The three dimensional strength and attractiveness that must have resided in the woman is not overly apparent in the two dimensional face of this collection. If the catalogue suggests something akin to a coolness for Ouida, perhaps the cataloguer has lived too long among the effects of others and wandered too far across the bridge from bibliography to biography.

The CollectionOuida Bergere Rathbone, who survived her husband by seven years, died in November 1974. After her death, the material in this catalogue was acquired over a one year span from two sources. The books were purchased from an estate buyer who had acquired them from the lawyer representing the estate. The scrapbooks, photographs, letters and other memorabilia were willed to the Actor's Fund. These were acquired directly from the Fund a year after the books. Again a few items were acquired from the estate buyer who had since acquired pieces of the collection from the Fund.

Solicitations to purchase elements of the collection before it was catalogued were refused. I wanted the catalogue to become a permanent record of what the Rathbones retained.

The collection is offered as it was acquired. Nothing has been added. Everything has been included except a Robert Louis Stevenson collection of poetry and a Phyfe photograph of Rathbone as Romeo. These were kept by the cataloguer. Nothing was broken down and pictures listed as extracted from scrapbooks were already in that state when acquired. Items were placed together so that material relating to a particular event or performance could be offered as a unit.

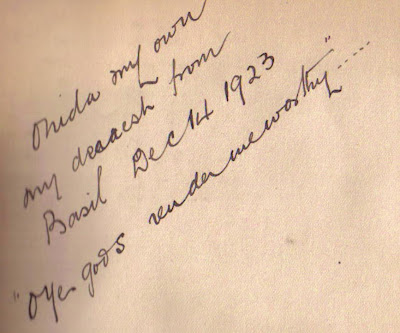

Rathbone's books were not kept in collector's condition. They were read, used and annotated. Those books without indication of Rathbone ownership have the following written in pencil on the front free endpaper: "Purchased from the estate of Basil and Ouida Rathbone by Gravesend Books, 1975."

.jpg)

The last house, perhaps, leaves from the late Town of Snoqualmie Falls.

The last house, perhaps, leaves from the late Town of Snoqualmie Falls.

(Cover art © by Terry Witmer)

(Cover art © by Terry Witmer)